Grief is a heavy word. When we hear it, we think that it must be tied to something tragic, like death. But grief need not be grand. Any emotions that are “caused by the end of, or change in, a familiar pattern of behavior” deserve the title, according to the authors of The Grief Recovery Handbook, John W. James and Russell Friedman.

With this expanded definition, it seems that we experience grief all the time. It’s when our favorite yoga teacher no longer teaches at the studio. It’s when we want to share an interesting article we read with a friend, but then we remember that they aren’t in our lives anymore. It’s when we pull up to Chick-fil-A on a Sunday. (That one’s a bit of a stretch, but you get the point.) The emotions are complicated and conflicting.

We learn how to get things, but not what to do when we lose things. The grief is there, but we don’t know how to process it. We may try to press it down, like a beach ball in water, and then cross our fingers that if enough time passes, the pit in our stomach will eventually go away. Time heals all wounds, right?

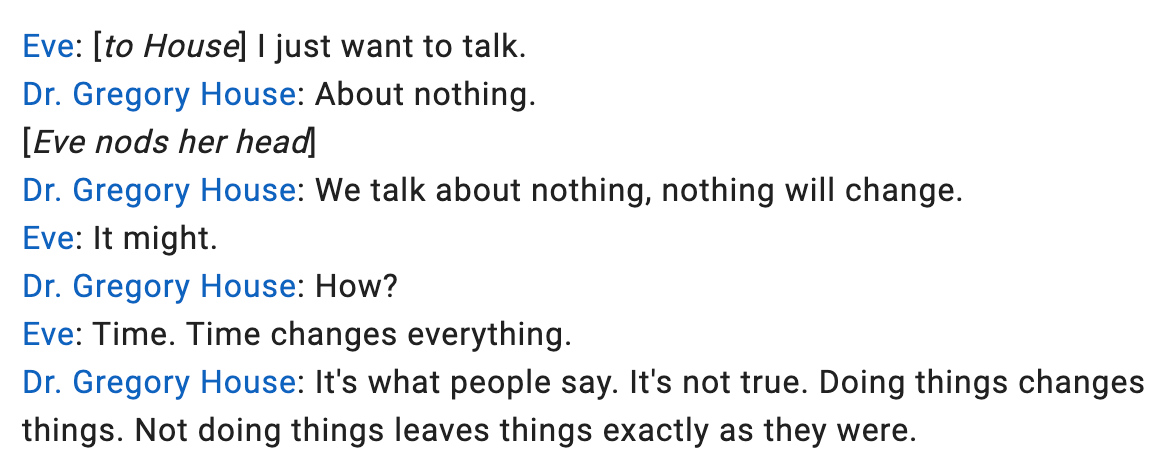

That’s also the hope that Eve, from the medical TV drama House, carries.

But Dr. House knows better. He knows that time alone cannot heal us. Yes, it’s a necessary component of the healing process that we cannot skip, but we also need to actively participate in our healing.

The scientist in me likes equations, so:

Healing = Time + The Stuff We Do With The Time

The formula is not complicated, but that doesn’t mean that it’s easy to implement. We cannot make time go faster or slower. We only have control over the second variable, and it’s what we do with the time that matters. The magic lies in the “stuff”— how we shepherd our healing process to give ourselves the possibility of becoming whole.

Naturally, this begs the question, wtf does “The Stuff We Do With The Time” consist of?

I have a few answers. But also I want to highlight that each experience of grief is unique to the person and situation. There is no universal salve for our wounds. Instead, each of us must experiment with different “stuff” to create a personalized healing concoction.

In my case, working with my therapist and doing the exercises in The Grief Recovery Handbook helped tremendously for the large ticket items — heavy baggage, if you will. Some exercises can be done solo, while others may be more helpful to do with a trusted partner, like a therapist.

I also meditate daily, even if it’s just a deep few breaths in the morning or throughout the day. It helps me center myself and be more in touch with how I’m really doing. Having implemented meditation into my morning routine for a few years now, I find that it works in times of both smooth and rough waters. I’ve found that to only turn to meditation during “in case of emergency break glass” situations is not likely to end well because it takes practice to recenter a mind, especially during tumultuous moments. I’m a forever student, of course, and I’m still learning how to sit with my emotions and navigate them as they come and go.

Lastly, there is also what the authors of the handbook call “short-term energy relieving behaviors,” or STERBs, which are common things that people do to bandaid the grief. These include, but are not limited to, food, drugs, sex, retail therapy, exercise, escapism (TV, movies, books) and workaholism. I often over-exercise (she’s a runner, she’s a track star), spend a wee bit too much time in Soho and either lose my appetite or overindulge my sweet tooth. And those are only the ones that I’ll admit to. But sometimes, we need STERBs to help us move through or around the pain. In the words of Haruki Murakami, “...we cannot simply sit and stare at our wounds forever.” My perspective is that using STERBs as a crutch is normal. And, as long as we do not stay in STERB-land indefinitely, and also do the aforementioned “stuff” that will bring us long-term grief completion, then I think we are doing pretty good.

Ultimately, as the two authors explain, “Time itself does not heal; it is what [we] do within time that will help [us] complete the pain caused by loss.” We must sit in the driver’s seat on the road to recovery — time sits shotgun.

If you enjoyed reading this article and want to support the newsletter, you can buy me a coffee here <3

It's really interesting that you brought up grief in this broader sense, not just tied to death, but to any loss of familiarity or rhythm. It made me think about how differently grief is understood and expressed across cultures. In Western contexts, grief is often framed as a deep internal process, something you sit with, work through, and eventually heal from over time. But in other cultures, the emotional vocabulary for grief isn’t always carved out in the same way.

Take Chinese, for instance. Words like 悲痛 or 哀伤 express sorrow or mourning, but they're often tied to specific events like death, and used in more formal or external contexts. There isn't really a direct everyday equivalent to "grief" that captures the kind of internal, psychological healing journey you're describing. Emotional experiences like grief are often folded into broader ideas of hardship or endurance, and aren't always named or processed as a distinct, lingering state.

It makes me wonder how much our ability to name a feeling shapes our experience of it. If we don’t have a word for this quieter, long-tail grief, the kind that comes from lost routines or friendships, do we still feel it the same way? Or do we move past it differently, because the culture doesn’t hold space for it in the same language? Some food for thoughts 💭